Interview for the AveFrance project. First published on April 15, 2020 here.

Olga de Benoist is a writer, photographer and dreamer. She runs the White Phoenix Tales literary club in Paris and the “People and the Cities” art project. Now she lives in Paris (for almost 12 years now). Her first book “The Age of Rain. Paris Stories” was released in September 2017. ” and presented at the Frankfurt Book Fair. It is a collection of short stories about Paris, music, lovers and dreamers.

She was born in a small Siberian town, grew up in Tashkent, lived in Russia, England and France.

This interview took place almost immediately after Olga had coped with yet another challenge in her life. Yes, Covid-19. We congratulate her for recovery from the bottom of our hearts, and we hope that our conversation will also help her a little at this difficult time.

I always try to determine the story before the interview and come up with a working headline in advance. And honestly, this time I didn’t get it right in advance. Maybe that’s a good thing. But at the same time, when I was looking through your materials, posts and publications, I had the feeling of some kind of journey. At the same time – a kind of magic. That’s why it’s a “Magical Journey” tentatively. We’ll see whether this title stays or not.

You see, I had the feeling that you were either inventing your life or depicting it in a way that created that feeling. Is that so?

Maybe my life is – magical? (laughs)

Maybe. That’s what I want to see if I got it right. For example, I read the following life story, it’s worth quoting:

“Olga Valeryevna VINOGRADOVA.

(May 29, 1985, Kiselevsk, USSR – May 28, 2089, Paris, France).

Russian and French writer, literary critic, photographer, artist, cinematographer and public figure. She spent her childhood and youth in Tashkent (Uzbekistan). She graduated from NSU Philology Department in 2008. Specialization is literature studies. In 2008 she moved to Paris. From 2009 she studied languages, politics, economics and law at the Sorbonne, obtaining a BA in 2012. From 2012 to 2013 she studied for a master’s degree at the University of Manchester. She was fluent in five languages and could speak and write Japanese and Portuguese. She has lived in Europe, Latin America, USA and Japan.

She is the author of collections of poems and short stories, for adults and children, nine novels, several monographs, books for children and collections of photographs. The golden period of creativity was from the 2020s to the 2050s. She described her creative work as “tangible prose”.

As a motto of her life she considered two of her favorite phrases: “Everything I want is everything” and “Who does not risk, does not drink… And whoever drinks, risks!

She died in her flat in the 15th district of Paris at the age of 103 in the company of her beloved husband Arnaud de Benoist and her cat Agathe”.

In the beginning it was fine, but I stumbled at the phrase “Freely spoken and written…” and when I reached the end, I was completely confused. But I was fascinated. What does this mean?

It’s actually a biography that I wrote many, many years ago, for a literary magazine. So I thought: why not write it as if my life had already happened? So this humorous biography spread all over the internet. Life will show how true it is. But I have outlined my main areas of activity and hobbies in it. I described what I would like my life to be like.

So yes, it’s a kind of magical journey. Since then, my name has changed, and my life has also changed a lot.

Life is cooler than any novel.

And you still have to write it!

I mean, it’s kind of like a plan. Has he changed much since then?

I don’t think so. So far, it’s working out exactly the way I wanted it to. I’m doing what I’ve always dreamed of – writing books. I organize events relating to literature, music, photography and art. I haven’t got around to filmmaking yet, but life is just beginning. For now, it’s my dream to make a film. Or maybe a film will be made based on my book someday, I don’t know.

Have you added any dreams?

Of course. There are new plans and new dreams. When we live, we dream about one thing, but as life goes on, we start dreaming about more, because new opportunities arise. It is like a field that is constantly expanding, the world is becoming more global, dreams are becoming more global.

Today I would probably say that I would like to be, first and foremost, a good person. At the time when I wrote this biography, I did not think about this. At that time, I wanted to have many achievements in my life. Now I would like to have more achievements in my inner space. I want to form myself more as a person than as a personality or a figure of action.

Rather, it turns out that it’s not the attitude towards accomplishments within you, but your attitude towards other people that has changed?

Yes. When we are young, we don’t think much about others, we think more about ourselves, what we are, what we want, what our boundaries are. We try to figure out who we are in this world. And as we get older, there is a desire to interact with the world around us. And all desires or dreams, I guess, they no longer concern only ourselves, or those we love. More and more they turn to our environment, the society in which we live. And they become more and more embedded in the universal history that we all make together, each in our own way.

So today, I would like to become a kinder person. To become the best version of myself.

And for it to manifest itself in some way towards others and help them, maybe…

Of course. And at the moment everything I do is about people. And my project Cities and People – I’ve been doing it for a few years now – I try to reflect the world I live in. Through the stories of people – writers, poets, artists.

And another project, The White Phoenix, a literary club, is also about people. About the meeting of a human with a human. About how we, inspiring each other to create, make this world a better place. And my books, which I am writing now and, God willing, will write again, are also not quite about me, but about something else.

Was “The Age Of Rain” about you?

“The Age of Rain” wasn’t really about me either. A lot of characters appear in it that are nothing like me – immigrants, locals, old people, young people, even a little girl… But it’s still, of course, a reflection of me to a certain extent.

Was this change in perception of the world, this correction to dreams, an important moment, or did it happen gradually, over a long period? Maybe the recent coronavirus had such an impact?

I think all changes, like everyone else, happen gradually as you get older. Although, of course, sometimes changes happen faster. When we go through crises, when we face a problem – like an illness, for example. That’s when we change as quickly as possible.

When I got coronavirus, of course I was scared, because I had what everybody is afraid of nowadays. It was a shock for me. I was very ill, and I’m glad it finally went away – but at times like that, of course, you look back and think about a lot of things.

You think about the kind of person you are, what you have done in life, what you could still do. And can I say that life up until now has been the way I would like it to be.

On the one hand, I said to myself, yes. There was nothing in my life that I would throw away. On the other hand, in moments like this, when you look into the face of your fear, it gives you the strength to go on living with more awareness and more honesty. To use my time for what really matters.

I agree. Let’s go back now from your biography-epitaph to the beginning of the journey. A magical one, we’ve decided. To the beginning of the road to Paris. Was there an occasion that drew you to Paris?

I had no intention of living in Paris at all. It wasn’t a dream. It all started when I was 18, I was studying philology at NSU at that time and I had to choose one of the languages. We were offered a choice of four languages – English, French, Italian and German.

I had studied English for many years, but I thought why not try French? I adored French culture, French films and I have read almost all the classic French literature. But I never thought I would study the language. And then that moment, that choice, made literally in five minutes, turned everything upside down.

I chose French and studied it for five years. Then I started working as a journalist, and at some point I thought there was something missing in my life, I wanted adventure, I wanted to see the world. So I came to Paris for a language course. For a year, as I thought at the time. I arrived, by the way, with only 100 euros in my pocket because of my mistake with the ticket – my name was not on the passenger list, I had to use all the money I had for the first time in France to buy a new ticket at the airport. It was an amazing challenge to come to a strange city where no one knows you and no one is waiting for you, and to survive with almost no money.

I liked Paris very much. It seemed so familiar to me. I kept walking around the city, through its streets, and in a moment I felt that I hadn’t felt so at home anywhere. Not because it was so beautiful, but because it was in its streets that I felt alive, that I could taste life.

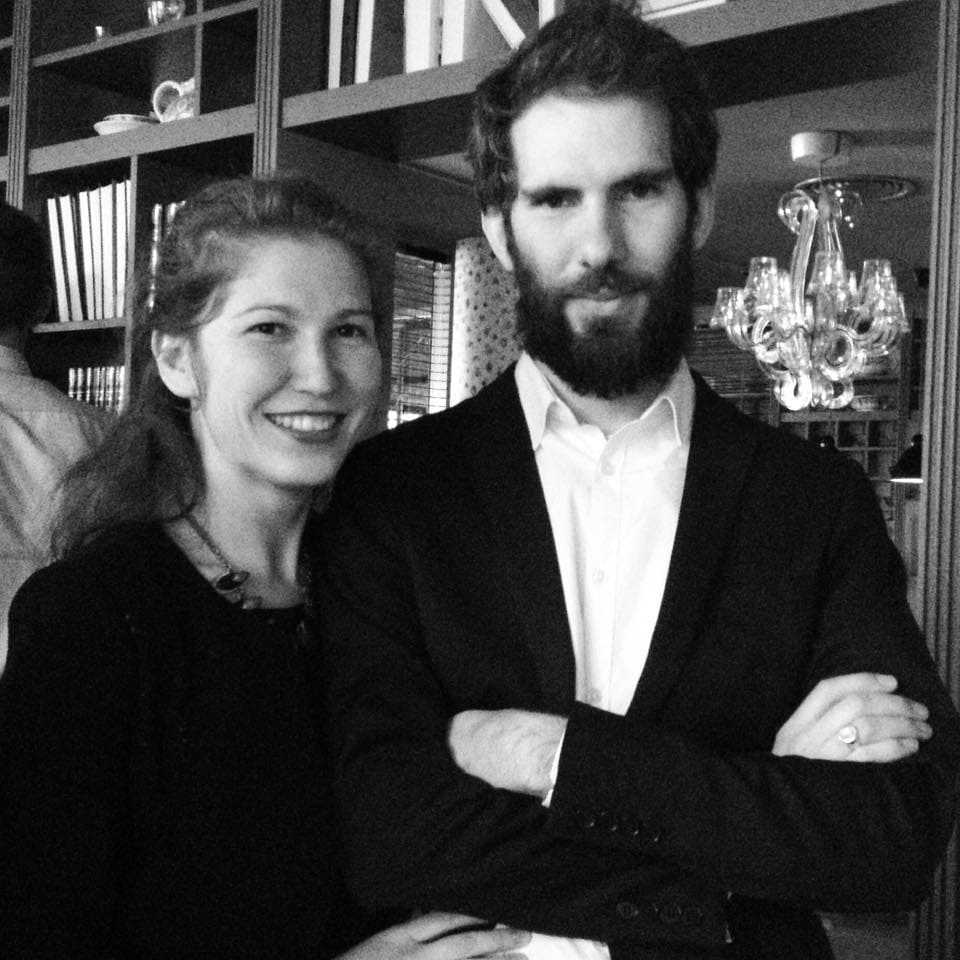

I decided to stay there, I enrolled at the Sorbonne, I graduated, I met my love – my future husband. And I realised that France would be – for the moment – my home.

Did this decision come before you met your future husband or afterwards?

You know, at first life in Paris was so difficult, a real adventure on my part, that to prove to myself that I could, I decided to stay in France in spite of everything. In Russia, I worked with words – I was a copywriter, a journalist, the editor of a music magazine that my friend and I created. In France, I was a nobody. I had to start all over again. And I wanted to prove to myself that I can, that it’s not just a new experience, but more. Then I met my future husband, it was love at first sight, and the thought of returning to Russia finally lost its meaning.

And everything came to a head, friends appeared, a job, I sprouted roots in this country. I recently obtained citizenship. France has long been my home. A second home. And I love it very much. Although Russia will always remain in my heart.

Is France or Paris your home? After all, there are ‘two big differences’…

I really love France – it’s a garden country, a beautiful country with everything, every imaginable and unimaginable landscape. And there is, of course, Paris. It’s a magical city. And I think those are my two loves – Paris and France.

An immodest question, perhaps… Do you hardly make your living from writing?

Very few people make a living from writing. Most writers do something else. We’re talking about Russian writers first and foremost. Because the American book market, for example, is a bit different. But all the same – it’s hard to make money with creativity. It brings me some income, I have signed contracts with a Brazilian publisher, with a Swedish one.

But that’s recent…

Yes, and you can’t live on that either. I work as a project manager. In general, I have tried many professions, I’ve been a journalist, a specialist in marketing, an organiser of festivals and exhibitions, and a smm-specialist. And I have been running projects for a few years now, and I love it. I worked at Renault, now at Carrefour (Carrefour SA, a big retail chain – note AF). At Renault, I worked in the innovation department, we worked on the ‘autonomous car of the future’. And now, at Carrefour, I also work on innovative projects.

That’s what I like to do. Being a writer isn’t really a profession. It is a mission. Look at A.P. Chekhov, M.S. Bulkagov, the Strugatsky brothers. They all had professions apart from their creativity. Profession – it allows us not only to feed ourselves, but also to gain the experience we need to write books. If we don’t know life – how can we write about it?

Of course, many writers would only like to write books. For now, unfortunately, that’s not possible. But who knows?

Do you manage projects?

Yes. I run several teams, which incidentally helps me to run our The White Phoenix Club as well. It also brings together a large number of people with different characters, experiences, expectations. My skills help me a lot in creativity as well.

What is “The White Phoenix” to you? Is it not a kind of diaspora or something?

I would say it’s something of an order. I called it so jokingly, the Order, three years ago, when I set it up with my friend, a writer and a singer Lena Yakubsfeld. The idea was to create a kind of literary salon. You know, centuries ago, there were salons in France (a very old tradition) where writers, poets, artists would meet. They would meet to share their work and this interaction, this exchange would create something bigger, and that bigger would become a cultural process.

And that’s what we do – we organize concerts, readings, exhibitions, we meet in a common art space. Even before the coronavirus crisis, the plan was to go to New York, London, Kiev and Moscow, and we were invited everywhere, so we had already started ‘touring’. Although now, of course, our activities have come to a halt. But it will all come back.

It will definitely come back. So you have communication in the second place, but professional interaction in the first place?

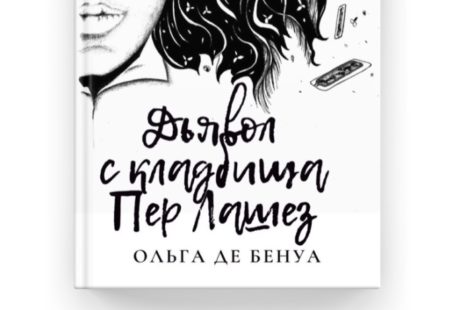

Yes. We meet every month, we read texts and take them apart. Thanks to that, I wrote my novel The Devil from Pere Lachaise which I read regularly during the meetings. Many of us have finished books on which we worked for a long time. Under the influence of “each other’s voices” we begin to create in a slightly different and better way. And, most importantly, a creative person, an artist really needs this kind of intensive communication with his or her fellows. We are all, in essence, loners. And for us, these meetings are an opportunity to become more complete, or something … to receive a response, to meet the other. And to support that other.

Olga, I’m looking at one of your posts on Twitter – I’ll quote it in full:

“1 job, 5 projects, 4 online courses, 1 business, 1 book in progress, editing 1 sb., 3 interviews, turn in an article, finish two stories and submit, sports, swimming, books, translation. Johnny says: you’ve always been a bit hyperactive. And I say: how do you get through the summer and not go crazy?”.

A trivial question: – Aren’t you spreading yourself too thin?

No. Generally, I think there are two types of people. There are those who need to concentrate on one project in order to finish it – and, by the way, not everyone knows how to finish them… And there are others.

Do you finish all your projects?

I almost always finish them. Unless I realise that it leads nowhere, in which case I give it up. But I have many things to do at once. I rest, switching from one to another. And it helps me every day to move forward in small steps. And after a year, suddenly some projects are finished, more than one, and you can start something new. But this is my way of working – and living. My husband, for example, cannot do it that way. He devotes himself entirely, entirely to one thing, to what he’s currently doing. To each his own. The main thing is to make it work.

I understood from your notes that he is a sculptor. Let’s talk a little about him and your surname – is it by your husband?

Yes. Olga de Benoist. But Arnaud – he’s not a sculptor. He was a sculptor many years ago, when I met him, unfortunately, he stopped. He’s actually an architect, but by first profession he was a bricklayer, a “companion”.

Companionage (inset AF):

There’s nothing like being a member of the famous workshop craft brotherhood, the companionage. Companionage still exist today, bringing together 45,000 people, and in 2010 the practice was listed as an intangible heritage of humanity protected by UNESCO. Bricklayers and roofers, carpenters, jewellers, stained glass artisans, shoemakers and blacksmiths have their companionage in dozens of trades. To be a Tour de France companion means to be a true craftsman and if you have a companion roof on your property then rest assured that it will last until your distant descendants.

The Tour de France, in which artisans take part, should not be confused with cycling. It’s not the means of transport that counts here, it’s the goal. At one time apprentices – young men and almost all children (once taken to the craft from the age of six or seven) went from one master to another, and were trained in skills and abilities. The apprentice had to create a masterpiece to be approved by the masters, and then he would become a master himself: he would receive a traditional staff, colours to wear for life and a nickname to be called and respected by fellow masters during gatherings.

In his youth, my husband learnt stone work from his companions. They are the best craftsmen, thanks to whom France has an enormous architectural heritage. They have their own traditions and rituals, including the famous journey through France that the apprentice has to take on foot at the end of his training.

Benoist is a famous, old family name, with many branches. Which Benoist are you related to?

There are “Benoist” artists who are not related to us, and then there are “de Benoist”. Arnaud, my husband, belongs to an old noble family. Their family tree goes back to Jeanne d’Arc. Interesting fact, she has been a very important character for me since childhood, a very important personage, I adored her and read a lot about her. It’s amazing what paths life takes us down sometimes.

There’s a famous philosopher and writer, Alain de Benoist for example – he’s my husband’s uncle. The most wise, the most interesting man.

This is an interesting point – in one of your publications, you give your view of what a Russian book should be like to interest a reader from another culture.

Well, that’s my subjective opinion, of course…

Yes. But aren’t you contradicting yourself? You write that there should be “an authentic and attractive immersion into the atmosphere of another country, another world, into the soul of a Russian person”. But does “The Age Of Rain” immerse into the soul of a Russian person? Then, after all, is Olga de Benoist a Russian writer now, or not quite anymore?

I wasn’t talking about my book. I have been living abroad for most of my conscious life. Of course, I’m not really a Russian writer anymore. Even if my book is written in Russian, it’s more of a Western book. I was talking about those who live in Russia and write about Russia.

When I was at the Frankfurt Book Fair, I discovered with surprise that it is very difficult to interest foreign readers in modern Russian literature. There were very few foreign visitors to the Russian official stand. Why? Because there is no such enthusiasm for Russian literature as there used to be… Today, if people in the West (or the East) read Russian literature, they mostly read the classics.

I wanted to say in that interview that if we want to take such a place in world literature again – maybe we should turn around a bit? Stop writing about purely Russian political realities that are incomprehensible to foreign society and write about things that are understandable to everyone, or so that they are understandable to everyone. If you look at Marquez or Hemingway – they wrote about their countries, and about politics, and about people, they wrote with great interest and love, but in such a way that their characters and these descriptions were understandable and interesting to anyone, no matter where they lived. There are universal issues, and books that work with them never get old. It seems to me that contemporary Russian literature lacks this.

I would like to have modern Russian literature read by everyone, Europeans, Asians and Americans alike, it’s important to me, maybe for my national pride.

But you consider yourself less and less of a Russian writer?

Yes, because I almost never write about Russia and I see the world from a Western perspective. The Russia I remember or “glimpse” of when I visit is not the one you probably know. To write about a country honestly one must live in it. So I’m not a Russian now, but I’m not a European writer either. Like many emigrants, I’m currently sitting “between two chairs”. It’s not easy.

Then whose worldview are you describing?

A person like me. A cosmopolitan who was born in one country, grew up in another, studied and lived in a third and a fourth. For him there is the Motherland dear to his heart, but at the same time he is interested in the whole world.

You, to quote one review, “like the Frenchs, their vagueness, their randomness, their lack of system…”. Is that really so?

It’s true. Although I wouldn’t say it’s directly disorderly, the Frenchs are not too organised. In general, they know how to work, how to live, and how to enjoy the present moment. In a way, they are a nation of hedonists. This, of course, is my personal opinion, but I like the French in this way. I like the way they live, eat, love…

Does your Frenchman next to you share your opinion?

You know, it is always easier to admire another nation than your own. He is very fond of the Russians, and so, of course, he will say that the Frenchs have a lot of disadvantages. All Frenchs love to criticize their country – just like the Russians, we are alike in that. But we are similar in that no matter how much we criticize our country we are still proud of it.

Well, it seems to me that French and Russians are similar in many respects.

I agree. That is why our cultures have been friends for many centuries, and we have similar views on many things – although there are differences, of course.

When this coronavirus detention is over – what’s the first thing you’ll take up ‘in freedom’?

I guess I’ll just leave home and wander the streets of Paris. Wherever I can see. I’ll go to cafés, I’ll go around my favourite places. Trocadero, Saint Michel, Montmartre. I’ll sit on the terrace of a bistro with a glass of chardonnay and squint at the sun. To know that everything is still in its place. To feel again that taste of freedom and carefreeness that we now seem to have lost.

Tell me, hasn’t Paris ever disappointed you?

Of course it has. It happened during rush hour on the metro and in other situations. Even the people and places we love the most disappoint us sometimes – but then we get “enchanted” back and life goes on.

One last question, I ask almost everyone. Who do you feel you are in France? Are you an emigrant, a traveller, a resident, an expat…?

I think it’s all just different facets of me, I can hardly single out one.

Maybe it’s already called “French”?

It’s just called ‘human’.

Anyone interested in our guest, her work, projects and life is welcome to visit Olga de Benoist’s website.